|

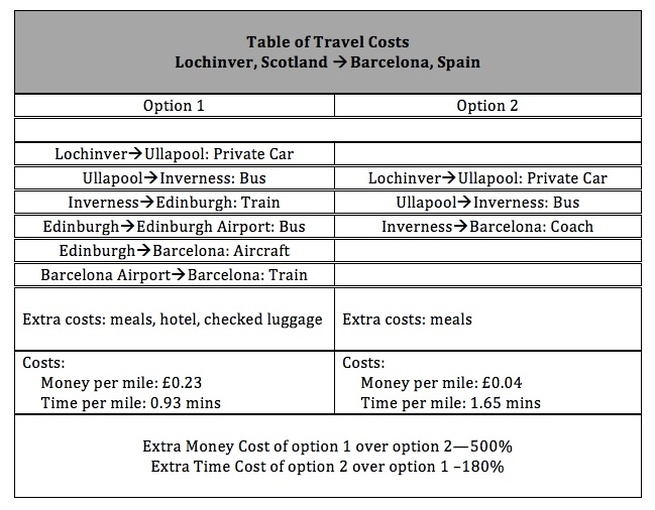

Calculating the cost of travel is not a straightforward economic exercise as it comes with a variety of categories such as money, time and effort. Some of these costs are private costs, and some are merely opportunity costs. Travelling is understood to cost money, but the other costs can be overlooked in the effort to part with as little of one’s hard earned cash as possible. Costs, both quantitative and the qualitative, add up differently for everyone based with individual preferences determining which costs you are willing to pay. Henry David Thoreau once said that the cost of anything is the amount of life given up in exchange for it and it seems that learning what costs you are willing to pay-- as well as those you are not-- is a valuable lesson to learn while traveling. There are several ways to define travel and each approach gives some insight into the costs that can be associated with travel. It most often refers to the activity of moving from geographic position A to geographic position B, with the best efficiency resulting from a combination straight line travel, zero interchanges and high speeds. The resulting costs: money, time and effort. Often the fastest, easiest or the most time efficient travel will cost you the most amount of money while the slowest journey with the most interchanges will be the more frugal option. What you are willing to pay is sometimes determined by the urgency of reaching the destination or the total effort you are willing to expend. For some, time has its own currency and the seemingly cheaper upfront costs of travelling the slower journey have high costs in time lost for another activity. A slower mode of transport might not be worth the higher relative cost of time and therefore cash is forfeited in order to save time. For others, the extra effort expended in transfers, layovers and changes in modes of transport is not worth the apparent lower cost of travel and they are willing to payer higher money costs to buy the apparently easier journey. Although the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, this course of travel is rarely an actual option unless moving across very short distances. Rather, travel is more accurately described through a second definition in the idea that travelling involves a journey, which includes the sometimes long and difficult process of change: change in location, change in environment and change in self. The associated costs: money, time, and life. Rather than the costs of just moving from position A to position B, the real costs are the combination of money, time and the stealthier cost of the value detracted from (or added to) the life of the individual. The choices one makes in the determining efficiency of the costs of travelling in part determined by what life the individual is willing to exchange. Is the individual most willing to part with free time, or with money requiring time and labour to earn? What added value will be contributed from experiences encountered throughout the journey? The time and money costs are easy to quantify but sometimes the life costs are more difficult to evaluate. For example, on a journey travelling from Lochinver, Scotland (geographic point A) to Barcelona, Spain (geographic point B) on a bank holiday weekend, I was faced with evaluating the costs that I was willing to pay for my travel. The easiest place to start is with a breakdown of time and money costs for the most expensive (aside from chartering a private jet!) journey in money terms compared with least expensive route. Here are my travel options: Call me crazy, but I opted for the 44 hour, £70 Option 2 over the 24 hour, £353 Option 1 not because I longed to spend 44 hours on a coach and not because I didn’t have £353 in my bank account. This choice was made on the assumption that in addition to a fatter bank account, I would also ultimately have a more fulfilling journey (with a story to tell!), as well as slightly less expended effort by taking this choice. So yes, it cost me nearly an extra day in time, a resource that I cannot regain nor know how much of it that I have remaining in the balance. However, this time was spent in gaining many new experiences: admiring the twinkling lights around the moonlit Edinburgh Castle, my first Chunnel crossing on the car train, watching the sunset with the Eiffel Tower as I journeyed through Paris, a bit of cloud spotting over the French vineyards and wondering at the geostrategic implications of the mountains forming the border between France and Spain, helping to keep the latter safely out of the World Wars. When I arrived in Barcelona, I was greeted by the same glorious sunshine I would have found had I arrived a day earlier, possibly less tired, but certainly poorer in both money and experience. If Thoreau was right, I am richer from this journey by adding to my quantity of life from the addition of these qualitative experiences. And after all, travelling is really the about the journey more than it is about getting to the destination. #travel #philosophy #economics

1 Comment

Big Mac Meal in Buenos Aires Big Mac Meal in Buenos Aires Making comparisons between civilizations is impossible for the traveller to avoid and it is easy to make evaluations in favour of one’s own civilization, because it is after all, one’s benchmark for normal. Paul Bowles claimed the difference between the tourist and the traveller is that the traveller makes comparisons between his own ‘normal’ civilization and the ones they encounter, rejecting elements not to their liking. These comparisons often begin with food or the availability of free wifi, but with the origins of the word travel rooted in terms meaning to travail, to be a traveller is to accept the assignment of not just experiencing new foodstuffs and places. Rather the assignment is to sift through this collection of experiences, adopting the valuable and rejecting the dross, resulting in a sort of pick n’ mix collection of civilization to take home. As a child of the granola generation, I have long considered McDonald’s to be one of those elements of my civilization that should be rejected. However, visiting the golden arches in various countries around the world, sometimes due to sheer necessity, I have learned that there is also merit to be found within this seemingly morbid establishment, even if it is a contemporary icon of the long held and much misaligned mission on the civilizing of nations. In much the same way as Christianity mixed with pagan traditions to make it more palatable to the converted savages, even McDonald’s cannot prevent local cultural influences from worming their way into this franchise whose global success is in part is determined by its standardised brand recognition. Although largely offering America’s supposed favourite food around the world, in itself raising questions about the actual condition of supposed civilization, region specific culinary preferences can be found on McDonald’s menus in exotic climes. In Peru, where McDonald’s can choose from 38 types of locally grown potatoes, an order of French fries is complemented by aji criollo salsa while the nearby drying ketchup vat is primed only by the occasional tourist. Or perhaps, you’d rather forego the traditional spuds and have an unusual serving of fried yucca with your Big Mac meal? Some McDonalds in Argentina have at times had wine available for consumption, certainly a civilizational win. Meanwhile, in China, you can order rice for breakfast instead of that all-American stack of pancakes or have a surprisingly delicious red bean pie for dessert. In addition to identifying some differences in regional food preferences, the globalised Big Mac can be used to make useful economic comparisons between civilizations. The Big Mac Index, invented by The Economist, is a mechanism for measuring purchasing power parity or what they describe as ‘currency misalignment’. Strip away the fancy terminology and what this tells you, is how much Big Mac your $4.79 (the control price of a Big Mac in the US) will buy you in other countries. This currency misalignment, which is apparently a bad thing in the material measurements of the progress of a civilization, is a very good thing to the traveller on a shoestring budget. Evaluating the comparable cost of living in different locations certainly requires the traveller to question the value of things within their own civilization, but in the short term, the Big Mac Index is a tool to estimating how far their budget can stretch in different economies. Although useful in many large cities, there are some pitfalls with using the Big Mac Index as a measurement for one’s relative wealth in economically valuated lesser civilizations. For example, in Argentina, there is purposeful undervaluing of the Big Mac in Buenos Aires’ McDonald’s as it is known that The Economist will be checking and publishing this price—making it appear that purchase power parity is better than it really is. In addition, bans by Argentine government on foreign currency purchases has created a black market —or a ‘blue market’ for foreign currency exchange. As a result of the blue market, a Big Mac in Buenos Aires, in reality only costs the traveller a mere $2.15 in November 2014—less than half of the price of a Big Mac in the US—creating the fallacy that the cost of living in Buenos Aires is half of some parts of the U.S. So while living expenses may be unexpectedly high, you can eat for cheap if you can survive on a single item diet. As with many establishments in tourist catchment areas around the world, even in McDonald’s there is sometimes both a local price and a ‘gringo’ price for that iconic Big Mac. In Cusco, Peru, local citizens get a 20% discount rate—which if you follow the economic thinking of the Undercover Economist—is a way of price targeting a one off market. The gringos who frequent the McDonalds’ in Peru are doing so not only because of the familiarity of the product but also perhaps in the misaligned belief that it is ‘safe’ from potential food poisoning risks—one of the supposed benefits of food safety standards found in 'real' civilization. Once a gringo has set their heart on the familiar tastes of home, there is probably little likelihood that the inflated price of a burger is going to deter this one time consumer from making an alternative choice, even if they are travelling on a shoestring budget. While adding new aspects for comparison as a result of the experience of travelling in new lands, the traveller cannot but help make extended economic comparison beyond those easily provided by McDonalds. Beyond enjoying the relative luxury that is now affordable in a different economic climate, this includes the realisation that living standards and perceptions of material necessity differ greatly from one civilization to another. Sometimes the biggest shock of being a traveller comes not from visiting a new civilization, but in returning from a ‘developing’ civilization to a ‘developed’ civilization only to be reintroduced to the waste and excess from the vantage point of having seen the other side. If the true traveller can reject any element from a civilization not to their liking, given the numbers of people who merely return to the practices of their former life after time abroad, perhaps the world is not full of travellers, but is rather only full of tourists after all. #philosophy #economics |

AuthorCorine loves a good adventure. She's partial to wilderness, UNESCO World Heritage sites and wine. Based in the United Kingdom, she has roamed the trails and streets of six continents. This is a chronicle of her experiences, seasoned liberally with philosophical musings. Archives

June 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed