An Old Homestead An Old Homestead It may be that there is no place like home, but there are a few for who home is a nostalgic notion of past dwelling. It is also a sense of present belonging to a place. Both are elusive ideas, one in the past and one that is in the tenuous notion of a present that moves toward the future with every passing microsecond. It’s been said that home is where you hang your hat, where your heart is --or maybe it really is just the nicest word. Home is supposed to be the place where they understand you, or the place where you fit in, Most days, if you ask where home is, I can’t really say if it’s where I’ve been or where I am going, but it may be that home is probably really only where my boots are and a place of belonging that I create for myself. To be from somewhere is to indicate where your journey began. In that case, my home of the past is a small country ranch house surrounded by fruit trees and a garden, framed by the desert and bordered by mountains. Remembering this abstraction of home I can sense the smell the hot sage in the summer air, recall the silhouette of purple mountains against the sherbet sunrise or perceive the crisp sound of silence muffled in the winter snow. These ethereal sensory inputs inform my base identification of a home, giving a place to stick a pin in a map and fill the space on my birth certificate. But I cannot return to this home, because it no longer exists. Most of the environment still remains, but all else has changed. Once you’ve left, you can never go home again because that version of home ceases to exist as an individual evolves. To be from somewhere can also indicate where you permanently inhabit or where your keep your worldly possessions. By these parameters, I am from a rain soaked island in a small sailing town that lays futile claim in being the sunniest of places in the green and damp of the British Isles. Here, there are no mountains and it rarely snows; the skies are often coloured the cold dull grey of dirty dishwater and the winter winds blow their fierce chill. This place is my home, or more formally, my domicile. It is where I live, though I might not be there in at any given present. Yet this home also changes around me as friends come and friends go and as I come and go returning a different person. For the wanderer, there has to be a different sense of home. Home is not only the place that you were born and the places where you have sent your post, but it is where your boots are located in the present. Home is a place of mind that is made up of a myriad of memories and experiences collected on the road. It is, no doubt, made up of the place that you’re from, but most importantly, it is the place where you are in the present. Belonging to a place can be determined only in the mind and what better place to belong than the place that you experience in this moment? Carrying home with you wherever you roam makes the entire world a very homey place. As time keeps moving away from the present and indefinitely into a future, the place that is home keeps extending limitless in a straight line to times and places that lie ahead. Home is the present/future rather than past and for those who wander away it is impossible to return to home because they have embarked not only on a journey of geography, but also on a journey of the mind. Rolling stones are continuously whittled and polished by the experiences they encounter, redefining a sense of self and likewise their sense of belonging. Perhaps a wanderer has a forwarding address unknown, but this particular is immaterial as home is truly only a state of being in the mind. Home is the place where I belong in the present progressing into the future, but it is also the places and moments where I can connect with my kith and kin. My community it not found in single geographic location in the place where I started. Rather, is it a collection of people with whom I deposit belonging, scattered across the time zones around the globe. The song says that you only hate the road when you’re missing home, but it is difficult to ever feel homesick because home is where I am, bolstered by technology enabling the frequent contact with one’s fellows. Lucky for me, home is everywhere that three taps on the heels of my red slippers and a good internet connection can take me. So while home may only be the present place of being for the wanderer, at least there is no complaining that there’s nothing to write home about, should you know where to send it.

0 Comments

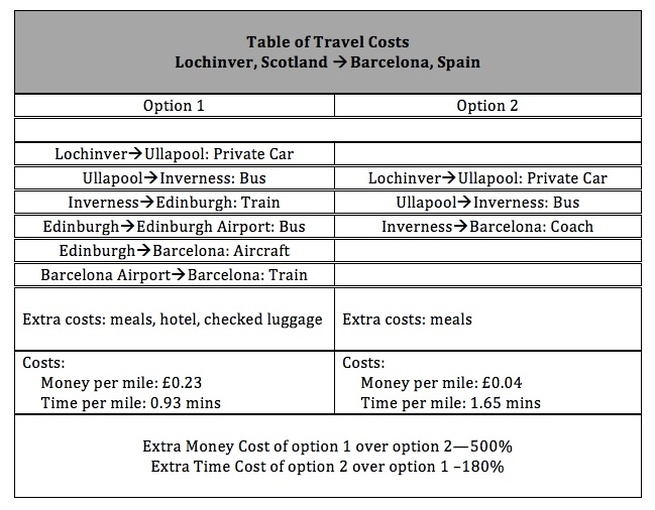

Calculating the cost of travel is not a straightforward economic exercise as it comes with a variety of categories such as money, time and effort. Some of these costs are private costs, and some are merely opportunity costs. Travelling is understood to cost money, but the other costs can be overlooked in the effort to part with as little of one’s hard earned cash as possible. Costs, both quantitative and the qualitative, add up differently for everyone based with individual preferences determining which costs you are willing to pay. Henry David Thoreau once said that the cost of anything is the amount of life given up in exchange for it and it seems that learning what costs you are willing to pay-- as well as those you are not-- is a valuable lesson to learn while traveling. There are several ways to define travel and each approach gives some insight into the costs that can be associated with travel. It most often refers to the activity of moving from geographic position A to geographic position B, with the best efficiency resulting from a combination straight line travel, zero interchanges and high speeds. The resulting costs: money, time and effort. Often the fastest, easiest or the most time efficient travel will cost you the most amount of money while the slowest journey with the most interchanges will be the more frugal option. What you are willing to pay is sometimes determined by the urgency of reaching the destination or the total effort you are willing to expend. For some, time has its own currency and the seemingly cheaper upfront costs of travelling the slower journey have high costs in time lost for another activity. A slower mode of transport might not be worth the higher relative cost of time and therefore cash is forfeited in order to save time. For others, the extra effort expended in transfers, layovers and changes in modes of transport is not worth the apparent lower cost of travel and they are willing to payer higher money costs to buy the apparently easier journey. Although the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, this course of travel is rarely an actual option unless moving across very short distances. Rather, travel is more accurately described through a second definition in the idea that travelling involves a journey, which includes the sometimes long and difficult process of change: change in location, change in environment and change in self. The associated costs: money, time, and life. Rather than the costs of just moving from position A to position B, the real costs are the combination of money, time and the stealthier cost of the value detracted from (or added to) the life of the individual. The choices one makes in the determining efficiency of the costs of travelling in part determined by what life the individual is willing to exchange. Is the individual most willing to part with free time, or with money requiring time and labour to earn? What added value will be contributed from experiences encountered throughout the journey? The time and money costs are easy to quantify but sometimes the life costs are more difficult to evaluate. For example, on a journey travelling from Lochinver, Scotland (geographic point A) to Barcelona, Spain (geographic point B) on a bank holiday weekend, I was faced with evaluating the costs that I was willing to pay for my travel. The easiest place to start is with a breakdown of time and money costs for the most expensive (aside from chartering a private jet!) journey in money terms compared with least expensive route. Here are my travel options: Call me crazy, but I opted for the 44 hour, £70 Option 2 over the 24 hour, £353 Option 1 not because I longed to spend 44 hours on a coach and not because I didn’t have £353 in my bank account. This choice was made on the assumption that in addition to a fatter bank account, I would also ultimately have a more fulfilling journey (with a story to tell!), as well as slightly less expended effort by taking this choice. So yes, it cost me nearly an extra day in time, a resource that I cannot regain nor know how much of it that I have remaining in the balance. However, this time was spent in gaining many new experiences: admiring the twinkling lights around the moonlit Edinburgh Castle, my first Chunnel crossing on the car train, watching the sunset with the Eiffel Tower as I journeyed through Paris, a bit of cloud spotting over the French vineyards and wondering at the geostrategic implications of the mountains forming the border between France and Spain, helping to keep the latter safely out of the World Wars. When I arrived in Barcelona, I was greeted by the same glorious sunshine I would have found had I arrived a day earlier, possibly less tired, but certainly poorer in both money and experience. If Thoreau was right, I am richer from this journey by adding to my quantity of life from the addition of these qualitative experiences. And after all, travelling is really the about the journey more than it is about getting to the destination. #travel #philosophy #economics  Big Mac Meal in Buenos Aires Big Mac Meal in Buenos Aires Making comparisons between civilizations is impossible for the traveller to avoid and it is easy to make evaluations in favour of one’s own civilization, because it is after all, one’s benchmark for normal. Paul Bowles claimed the difference between the tourist and the traveller is that the traveller makes comparisons between his own ‘normal’ civilization and the ones they encounter, rejecting elements not to their liking. These comparisons often begin with food or the availability of free wifi, but with the origins of the word travel rooted in terms meaning to travail, to be a traveller is to accept the assignment of not just experiencing new foodstuffs and places. Rather the assignment is to sift through this collection of experiences, adopting the valuable and rejecting the dross, resulting in a sort of pick n’ mix collection of civilization to take home. As a child of the granola generation, I have long considered McDonald’s to be one of those elements of my civilization that should be rejected. However, visiting the golden arches in various countries around the world, sometimes due to sheer necessity, I have learned that there is also merit to be found within this seemingly morbid establishment, even if it is a contemporary icon of the long held and much misaligned mission on the civilizing of nations. In much the same way as Christianity mixed with pagan traditions to make it more palatable to the converted savages, even McDonald’s cannot prevent local cultural influences from worming their way into this franchise whose global success is in part is determined by its standardised brand recognition. Although largely offering America’s supposed favourite food around the world, in itself raising questions about the actual condition of supposed civilization, region specific culinary preferences can be found on McDonald’s menus in exotic climes. In Peru, where McDonald’s can choose from 38 types of locally grown potatoes, an order of French fries is complemented by aji criollo salsa while the nearby drying ketchup vat is primed only by the occasional tourist. Or perhaps, you’d rather forego the traditional spuds and have an unusual serving of fried yucca with your Big Mac meal? Some McDonalds in Argentina have at times had wine available for consumption, certainly a civilizational win. Meanwhile, in China, you can order rice for breakfast instead of that all-American stack of pancakes or have a surprisingly delicious red bean pie for dessert. In addition to identifying some differences in regional food preferences, the globalised Big Mac can be used to make useful economic comparisons between civilizations. The Big Mac Index, invented by The Economist, is a mechanism for measuring purchasing power parity or what they describe as ‘currency misalignment’. Strip away the fancy terminology and what this tells you, is how much Big Mac your $4.79 (the control price of a Big Mac in the US) will buy you in other countries. This currency misalignment, which is apparently a bad thing in the material measurements of the progress of a civilization, is a very good thing to the traveller on a shoestring budget. Evaluating the comparable cost of living in different locations certainly requires the traveller to question the value of things within their own civilization, but in the short term, the Big Mac Index is a tool to estimating how far their budget can stretch in different economies. Although useful in many large cities, there are some pitfalls with using the Big Mac Index as a measurement for one’s relative wealth in economically valuated lesser civilizations. For example, in Argentina, there is purposeful undervaluing of the Big Mac in Buenos Aires’ McDonald’s as it is known that The Economist will be checking and publishing this price—making it appear that purchase power parity is better than it really is. In addition, bans by Argentine government on foreign currency purchases has created a black market —or a ‘blue market’ for foreign currency exchange. As a result of the blue market, a Big Mac in Buenos Aires, in reality only costs the traveller a mere $2.15 in November 2014—less than half of the price of a Big Mac in the US—creating the fallacy that the cost of living in Buenos Aires is half of some parts of the U.S. So while living expenses may be unexpectedly high, you can eat for cheap if you can survive on a single item diet. As with many establishments in tourist catchment areas around the world, even in McDonald’s there is sometimes both a local price and a ‘gringo’ price for that iconic Big Mac. In Cusco, Peru, local citizens get a 20% discount rate—which if you follow the economic thinking of the Undercover Economist—is a way of price targeting a one off market. The gringos who frequent the McDonalds’ in Peru are doing so not only because of the familiarity of the product but also perhaps in the misaligned belief that it is ‘safe’ from potential food poisoning risks—one of the supposed benefits of food safety standards found in 'real' civilization. Once a gringo has set their heart on the familiar tastes of home, there is probably little likelihood that the inflated price of a burger is going to deter this one time consumer from making an alternative choice, even if they are travelling on a shoestring budget. While adding new aspects for comparison as a result of the experience of travelling in new lands, the traveller cannot but help make extended economic comparison beyond those easily provided by McDonalds. Beyond enjoying the relative luxury that is now affordable in a different economic climate, this includes the realisation that living standards and perceptions of material necessity differ greatly from one civilization to another. Sometimes the biggest shock of being a traveller comes not from visiting a new civilization, but in returning from a ‘developing’ civilization to a ‘developed’ civilization only to be reintroduced to the waste and excess from the vantage point of having seen the other side. If the true traveller can reject any element from a civilization not to their liking, given the numbers of people who merely return to the practices of their former life after time abroad, perhaps the world is not full of travellers, but is rather only full of tourists after all. #philosophy #economics  Chinstrap Penguin Chinstrap Penguin Everyone loves penguins, but after visiting Antarctica I now have an altered perception of the half fish, half fowl creatures. When wearing black and white, penguins are in their most adorable form. Even after many repeated encounters, both explorers and tourists find it impossible to refrain from snapping obscene quantities of photos of penguins. One early 20th century explorer commented on hearing the continuous clicking of the camera shutter against the backdrop of Antarctic silence every time their expedition encountered a new colony of penguins. I can understand why this is possible as during my three short weeks in the Antarctic region—I managed a ridiculous 1500 pictures of penguins. Somehow, they were so enthralling as they waddled about on the ice and snow in their natural habitat and I pitifully tried to capture those moments on film. It seemed that every new penguin met was immensely cuter than the last and click went the shutter again. But the truth is that these seemingly innocent penguins have a dark side. Contrary to the representations of media and the film industry, penguins are not adorable bundles of black and white. Penguins are pink. Making their nests in a fester of fetid pinkish-red guano-- excrement benefiting from the richness of a seafood diet and the scourge of the penguin colonies. Guano, or saltpetre, used widely in food preservation, is a resource over which a number of wars have been fought. You read it right—penguin poop is a valuable economic resource as it is teeming with fertilizing nutrients. And there is a chance that you have eaten it. Many people worry about the nations of the world wanting to drill for oil or mine for other resources in the Antarctic—and the continent is probably brimming with economic opportunities buried underneath all that ice. However, when the Madrid Protocol came into force, prohibiting activity on mineral resources, the most accessible resource given up in the Antarctic was penguin excrement. It is difficult to imagine headlines announcing the ruin of the Antarctic for the pursuit of guano harvesting, so hopefully the pink stained icy penguin habitat is safe from economic exploitation for just a while longer.  Scavenging Skua Scavenging Skua Yet despite wearing these noxious pink stained suits, penguins are still interesting creatures and it sometimes easy to forget that they are really birds rather than some other flippered aquatic species. Possibly the only time that penguins are truly black and white is when they are in the water, hunting and playing. The next biggest surprise of meeting real penguins and discovering that they are pink--is the first encounter with the synchronised swimming of a muster of penguins in their natural habitat something that is never observed in their cramped conditions in zoos. I have watched endless video hours of penguins sliding on snow, swimming near shore and stealing rocks from other penguins—but I had never seen them swim in unison like a pod of porpoises until I visited the Antarctic. Evolution hasn’t permitted for penguins to fly, but they sure can swim—which is a handy talent for (hopefully) escaping from predatory leopard seals. Unfortunately, while on land, their usual pink masquerade doesn’t assist in defending the colony from the predatory activities of the menacing skuas lurking overhead, stealthily looking for opportunities to steal a tasty egg or a fluffy penguin baby.  Pink Penguin Sex Pink Penguin Sex In addition to being dirty pink birdies, although living in the purest and most untouched landscape on the planet—penguins are exceedingly filthy. In my short encounter with the Antarctic, I observed more incidents of penguin sex than I can count, and therefore also have a substantial quantity of penguin porn in my hundreds of penguin photos. It is almost impossible to distinguish the male from female penguins and so the joke circulates that you can identify females by the presence of pink muddy footprints on their backs as doggy-style is the preferred penguin position. However, even this identification system comes with a caveat. Penguins love their sexual activities so much—they’ll basically do it with anything, dead or alive. In fact, penguin sexual behaviour is so depraved that the Victorian polar explorers themselves turned various shades of pink and red when watching penguin sex and thus published their findings on penguin reproduction in Greek so that only learned gentleman would be able to read the reports. These reports weren’t published for the public until 2012, when of course no one but the Greeks can read Greek, but fortunately, penguin encounters are now accessible more than just the exceedingly privileged. The truth about penguins might indeed be that they are pink, valuable and filthy. But a second truth is that I love them even more for having experienced their reality and hope someday for another face-to-face encounter with these adorable avian peculiarities. #wilderness #PolarRegions  Seeking the Drake Seeking the Drake The Drake Passage, a 600 mile expanse spanning the Southern Ocean between Tierra del Fuego and Antarctica, is watery highway that has carried many explorers, scientists and tourists to the icy continent at the southernmost latitudes of the globe. Making way through this oceanic version of Hades, it is difficult to imagine what pushed the early explorers to prove the existence a place that once only existed in theory. My voyage was made in relative luxury compared to those who crossed in ancient wooden ships, without maps or GPS, in sea swells that towered over their trembling masts. While I wouldn’t trade ships with them, even if I could, I still envy their experience of uninhibited adventures, experiences that for the rest of us have been stripped by the conveniences of modernity. Like me, perhaps they suffer infection by the incurable affliction described as wanderlust. Yet despite the changing technology, for anyone who wishes to make acquaintance with the frozen continent, the Drake is still a rite of passage. Antarctica, labelled as Terra Australis Incognita or the unknown southern land on maps during the Age of Discovery in various imaginative forms, only became known to those who dared venture to sail through the Drake, some by accident and some with intent throughout the 19th century. Crossing the Drake in a modern vessel requires 2-4 days in the open high seas but for the explorers of auld lang syne, it required weeks of cold and miserable hardship in a vessel assailed by the mighty force of the Drake’s waters. Sailing due south today, Antarctica is clearly delineated on a map, making navigation to landing sites a relatively straightforward task. The original explorers set sail across the dread Drake, not even knowing land existed, sailing on expeditions fuelled by dreams and on the energy of the hope of discovery of new territory and resources.  Thanksgiving Day in the Drake Thanksgiving Day in the Drake The Drake is a fearsome thing. Experiencing a Beaufort 11 force storm, with waves cresting higher than my vantage point on the top floor of the Ocean Nova, I was awed by the power of the sea as it tossed our polar class ship from side to side, our able captain holding bow to the waves. Although never experiencing the storms of the Drake himself, Coleridge described it as tyrannous and strong. The poetic lines, while lyrically descriptive of the essence of the Drake, are insufficient to capture the experience of the passage. During this storm, I vacillated between comfort in knowing the sea around us was virtually empty as demonstrated by AIS data available onboard--and thus we were unlikely to be in an unwitting collision with another vessel, and also knowing that if an incident occurred, any help was too far away to be certain of salvation. Accompanying this to-ing and fro-ing of Drake storms is the near indescribable malaise experienced throughout the passage. Even if one does not succumb to the fullness of seasickness, the Drake drains all energy from the core of your being, leaving victims with black and hollow eyes. Many follow the practice of ‘dry Drake’, abstaining from alcohol to limit the effects of this strange sea-malady. It provided some consolation to learn one heroic explorer observed that the more intelligent a being, the more likely they were to succumb to the effects of the Drake --and I was exceedingly ill. Even many of those who boasted of many previous sea voyages without effect were influenced by its spell.  Ocean Nova in better waters Ocean Nova in better waters A benefit of exploration in modernity is the availability of drugs, substances intended to induce healing or to prevent suffering and never ever to be misused. There are some drugs that are better than others, and most have a drug of choice, including options such as caffeine and alcohol. But on the Drake, the drug of choice is merely anything that will help one to avoid seasickness—the harder the better. The first trip, I tried the softer antidotes for motion sickness, with the disastrous result of losing my breakfast during the delivery of a lecture on Antarctic history. The second voyage, I was prescribed the hard stuff by the ship’s doctor, resulting in the peaceful passage of the Drake in a near continuous bout of slumber. In the case of the Drake, drugs are always the answer. Passing through the Drake, with drugs or without them, gives the experience of two types of dreams. The first is of an exceeding malicious nature and is an embodiment of the essence of the Drake: the Drake introduces nightmares to one’s consciousness throughout the voyage. Mine included the horrors of the mass slaughter of orcas by bounty hunters, the black of their bodies prostrated against the sparkle of the Antarctic ice, stained with red from blood—a nightmare of the worse kind. The better dream that the Drake delivers is the realisation of a region so pristine and pure--a wilderness that envelops your being with enchantment and wonder. The Drake is certainly something to be survived, but when one does, the rewards are beyond any suffering experienced throughout its passage. And when one has finished the arduous journey, it is easy to see why some are compelled to repeat it again and again. *Thank you to Dr Sergio Pesutic for the comedic speech given before one passage of the Drake, introducing the conceptual combination of Drake+Drugs=Dreams. He was not wrong. #PolarRegions  Waving Palms Waving Palms Offering shelter from the hot summer sun, the Palmeral de Elche-- a UNESCO World Heritage site, rises out of the semi-arid landscape of the Alicante Province like an oasis with its thousands of palm trees splashing green against the brown horizon. The continued existence of the sprawling acreage of these palms, in a city where economic prosperity is based on mass industrialised shoe production, situated within a global throwaway society, represents a small triumph over the cupidity of humanity. Despite losing their economic significance and waning in cultural value, the palms of Elche still stand tall, waving their branches against the Spanish sun while progress churns on around them, serving as silent witnesses to changing times and representing a bygone age. The notion of heritage is permeated with the essence of all that this generation of man has inherited from their forefathers, including the good things of society, but also the bad—a list that includes those many social chains to which Rousseau refers. Heritage is often considered at micro levels—the genetic traits that stare at you in the mirror or in the museum objects that represent the history of a nation, but even this conception of heritage has roots in a greater narrative reaching beyond your nearest ancestors. The common heritage of mankind preserved through the designation of UNESCO World Heritage status, though located in a place outside of one’s familial or national borders, represents a site significant to the story of the entirety of the human race. As part of this common heritage, the Palmeral de Elche has survived the ravages of time as our once unique civilizations have expanded, merged and globalised into an integrated web of the international system.  After the Deluge After the Deluge Arriving in Elche just after a supercell dropped over five inches of rain in less than twenty minutes, the flashflood swirling around network of strategically planted palms made it a little easier to imagine the efficiency of this little oasis that once supported a vast agricultural zone. Likely introduced to Europe by the Carthaginians, the palms were eventually planted into a grid system by the Moors, along irrigation canals usually fed with water from the nearby Vinalopó River. Even with the orchards looking more like rice paddies after the deluge than part of a sophisticated desert agricultural zone, it was easy to see how the palms not only once provide nutrition and raw materials to the civilizations that they supported, but also offered a shaded garden where other foodstuffs such as pomegranates, grains and olives could grow. The palmeral oasis retains its importance by representing the transfer of culture and knowledge from one society, and from one continent to another—the sort of knowledge that improved the condition of people living in Europe. However the site, and ultimately its demise, also represents the ills of society and the fears of otherness. The palmeral system fell into decline when the Moors were defeated by the united Iberian kingdoms of Ferdinand and Isabella, and were ultimately expelled from Europe in events which closely coincided with the discovery of the New World and the dawn of the Columbian exchange in another boost of resources and knowledge for the old world of Europe. Thus, the palms also serve as a final reminder that collaboration and cooperation lead to greater things for all of humanity, while actions to the contrary contribute to decline and deterioration. Imagine how much richer this corner of Spain would be if the palmeral were still a functioning system! Instead, we’re only left with mass produced shoes and palm fronds waving in the wind. #Spain #UNESCOWorldHeritage  Castillo Nova Castillo Nova The Spanish countryside is dotted with a multitude of medieval castles, strategically situated on high vantage points overlooking the fruited valleys below. They stand silently portraying characteristics of Spain’s chequered and sometimes violent history with their time weathered resilience, meanwhile testifying to modern economic woes with their seemingly permanently locked portals. Inspired by the surroundings, it seems only a natural thing for four mature adults to return to the diversions of youth and to construct a sandcastle while in the coastal regions of the Spanish Med. But the rules of the game have changed: no longer can sandcastles be built with the carefree and reckless abandon of youth--they must now be carefully and meticulously constructed with all the training and professionalism that adulthood has infused into their membranes. Constructing sandcastles is no child’s play— it is serious business. So how many consultants does it take to build a perfect seaside sandcastle? The answer, most decidedly, is four. Any more and one would face the ruinous combination of too many chiefs, and any less would leave potentially catastrophic holes in the project. Fortunately for this castle, the project management team had an experience portfolio in manufacturing engineering, heritage, international affairs, and change consultancy. What appeared to be an afternoon of playtime on a sun soaked Spanish beach was in actuality a real world team building activity. As the castle rose from the sand, it quickly became apparent that respective areas of individual expertise were being implemented in the building of Castillo Nova in the roles assumed by each consultant throughout the delivery of this very important project. Stage 1: Planning Having determined that a sandcastle should be built to benefit general well being of the beachside denizens, to improve the local scenery and to make a claim to sovereignty over this small plot of beach amongst the hoards of other sun seekers, the consultants set out to design their castle. Over a preliminary glass of wine, it was discussed between the playmates that this castle absolutely must have a moat, ramparts, a keep, high walls with rounded turrets and most importantly of all—a tunnel feature. Due to its seaside location, the site would also need a protective sea wall, an exterior ditch. Optional features included: sand drip evergreen trees, seaweed for the plastic dinosaur accessories, battlements, and an artillery battery. Stage 2: Execution With four autonomous consultants embarking on the realization of this diminutive project, one would predict that conflict would arise over the division of labour, but instead each person quickly found niche areas to implement their areas of expertise while packing sand into buckets. The manufacturing engineer determined the optimal position of the defensive sea wall relative to the encroaching Mediterranean waves while the heritage expert advised on the positioning of the relative castle features appurtenant to the range of historical periods which this castle represented. Meanwhile, the international affairs expert formed the strategic defensive features of the dig in preparation for the probable impending doom that all sovereign entities must expect sooner or later. However, keystone to the smooth exchanges between these sand kings, was the role played by change consultant, who ensured that each individual had the tools necessary to complete their present task and removed any obstacles (such as excess sand or water leaks) to the jobs being finished. This holder of the spade, who appeared to generally be employed in the digging of the exterior ditch, was critical to the ultimate success of the project by acting as conduit for information and process transitions between the other team members. Stage 3: Evaluation Clearly, the best place to evaluate the completion of a seaside sandcastle is by swimming a distance into the briny deep. From this vantage point, the build can not only be admired as it towers above the foam, but it allows for a certain smugness to incubate while the swarms of beachcombers pause to look at its magnificence (and to perhaps wonder why a tyrannosaurus rex guards the keep and whether seaweed is an adequate diet for a stegosaurus). It was decided, that while the design itself was inherently sound, the integrity of the final project was undoubtedly subjected to some errors in calculations-- a possible side effect of the local wine-- including the inland reach of the waves and the lack of reinforcing materials for the tunnel feature, ultimately leading to its partial collapse when the defensive moat was filled. Yet deeming to have adequately conquered the amateur sandcastle scene, the team of consultants began to dream of competition sandcastles and not without the talismanic dinosaurs. In the meanwhile, they can be satisfied with their well-planned, culturally sensitive addition of the ruins of yet another castle to the motley Spanish landscape. #Spain #consulting #playtime While travelling through the coastal roads of the Spanish Costa Blanca, I reflected that these streets lined with seemingly abandoned and shuttered buildings might be the perfect training ground for the zombie apocalypse. Despite initial impressions deeming the entirety of the region as wasteland, there are three different distinct layers of civilization and thus three different opportunities for preparation training of the dread day when life essentials no longer include wifi and are instead framed by the lower layers of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. As any good wilderness adventurer knows, understanding the terrain and an intimate knowledge of the resources and layout of your environment is key to survival by ensuring those physiological and safety needs.  Populated Beach Near Denía Populated Beach Near Denía Although the pretty pictures on the tourism brochures tell you differently, Zone 1--the first layer of the Costa Brava in actuality contains the harsh realities of the urban wilderness. It is in essence a saturated microcosm of the pestilence of a consumerist society, full of the gullible humanoids that bought into those glossy falsehoods of contrived paradise to escape the macabre reality of modern life. Hardly a credit to biodiversity, the stereotypical alcohol saturated, sun-damaged tourists abroad who are supported by an ecosystem of trinket shops and eateries with imitation global cuisine have a destiny for when the apocalypse arrives. Despite the initial repugnance and an overwhelming desire to flee this urban zone for the wild expanses of the backcountry, a quick visual survey soon reveals that the coastal strip of horrors can be utilised as a zombie containment zone in a reverse siege. There will be unfortunate casualties in the initial abandonment of this zone—including the small pockets of well-hidden cobbled streets housing cafes serving seafood paella made with locally grown rice and the shaded bars offering olives, tapas and regional wines as a post siesta respite from the heat of the Spanish sun. However, these traditional features are also found deeper in the interior, and so the entirety of Spanish culture and civilisation will not be lost by the defense in depth use of the coastal zone. Perhaps when the zombies have been eliminated, the resources of the sea and the beautiful white sands can again be enjoyed sans the scourge of red herring touristy morsels that will thankfully sustain the invading zombies while one makes a timely exit to the next security sector.  Rice fields from Cookie Cutter Urbanization Rice fields from Cookie Cutter Urbanization Zone 2, or the buffer zone, is the next layer of this regional gradation and it demonstrates a melancholy hybrid of the serene sun-soaked landscapes of the Spanish countryside and the horrors of careless and unbridled economic development. Delineated by a toll road, government protected lowland nature reserves and mountains, this zone is populated by expats dwelling in cookie cutter urbanizations-- enclaves of resistance to Spanish cultural influence-- and the last of the local farmers struggling to secure a livelihood through the cash crop production of olives, citrus fruits and wine for markets abroad. This environment is dotted with villages forced to face the realities of an economy that relies on these expats with their foreign cash infusions, resulting in a high ratio of Chinese takeaways, grocery shelves stocked with foreign imports and airwaves filled with English-language radio stations. While an important sector in terms of the availability of foodstuffs, during the zombie apocalypse, this zone otherwise provides benefit only in its use as an escape corridor and some higher altitude vantage points from which to safely observe the desolation below.  Abundant Non-edible Sea Squill Abundant Non-edible Sea Squill However, the real gem of the Spanish Costa Blanca is found in Zone 3, an area displaying the natural and cultural heritage of this region and making it an ideal place to survive the zombie apocalypse in both its resource supply and defensive positioning. The strategic eye will see the old military turrets still positioned on mountain chokepoints and a network of well-worn trails lead to trusty watering holes, including the many freshwater fonts hosting large contingents of frogs. The dry, arid landscapes are an excellent representation of the biodiversity of the Mediterranean coast; the Hermes oaks typical of the region, wild herbs and asphodels are all ultimately edible and the narrow valleys are lined with figs, brambles and nut trees watered by natural springs, locations signalled by reeds and other water plants. The natural abundance of this zone, despite the hostility of the summer sun, certainly makes it an attractive position for ensuring survival. Additionally, the zone is sparsely populated by small villages, often drained of former inhabitants who have left for work in the big cities. The houses in these sweet pueblos are built around beautifully tiled courtyards with small kitchen gardens which can be seen through waving lace curtains and street doors left ajar. The village square still displays cross sections of traditional Spanish culture: old women gambling with coins in one corner and clucking at the children playing with balls while the old men occupy another shady corner with their smokes and cañas. When the marauding zombies deem fit to leave the morbid fleshiness of the coast for this interior destination, they might find themselves wishing to evolve from their undead human form, mesmerised by the winsome nature of the Costa Blanca before the onslaught of modern progress and touristic contamination. #zombieapocalypse #survival #wilderness #spain |

AuthorCorine loves a good adventure. She's partial to wilderness, UNESCO World Heritage sites and wine. Based in the United Kingdom, she has roamed the trails and streets of six continents. This is a chronicle of her experiences, seasoned liberally with philosophical musings. Archives

June 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed